AI (Artificial Intelligence): Computer systems that can perform tasks that typically require human intelligence, such as understanding language, recognising patterns, and making decisions.

Algorithm: A set of rules or instructions that a computer follows to solve a problem or complete a task.

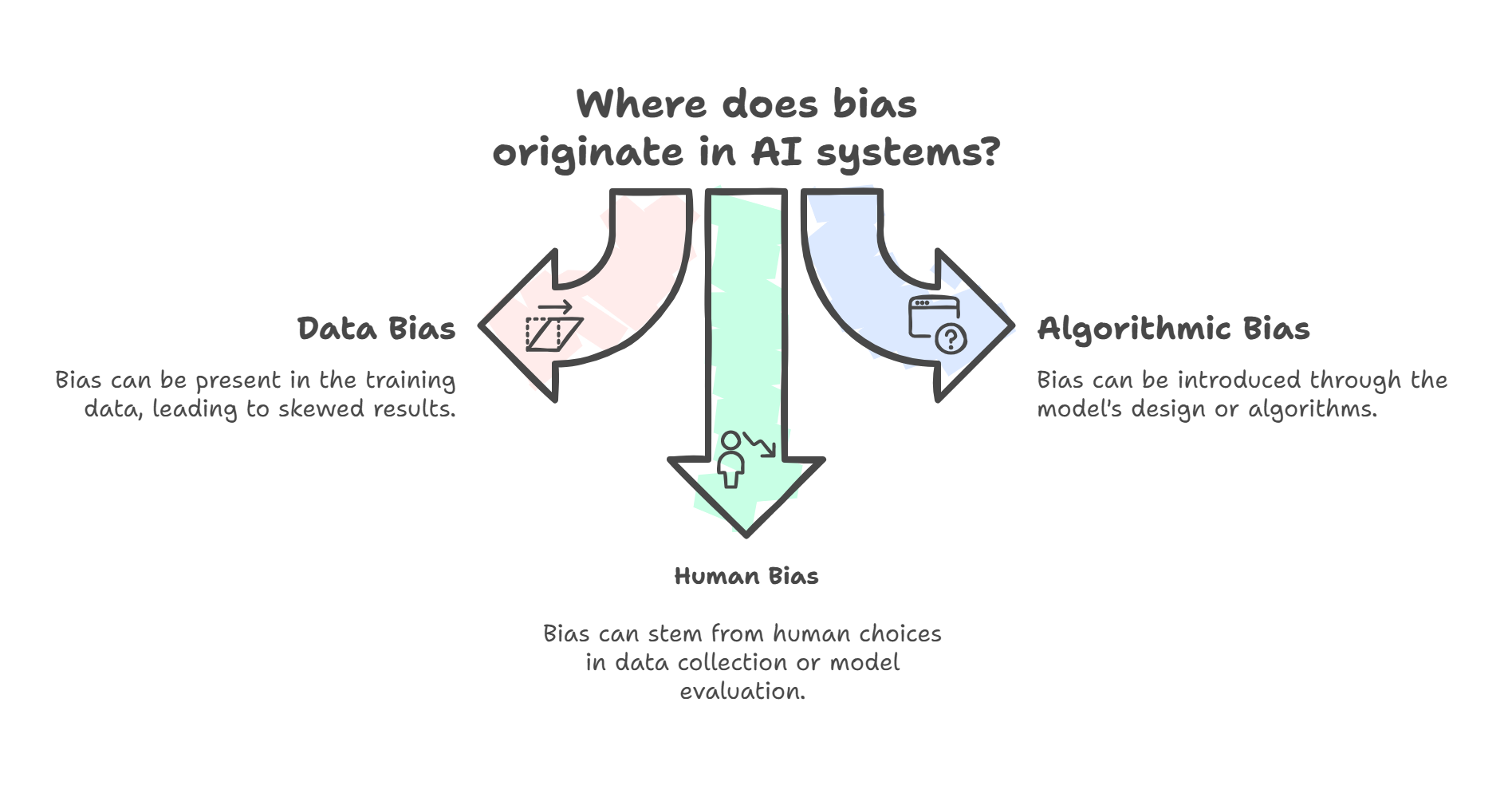

Algorithmic bias: Systematic and repeatable errors in AI systems that create unfair outcomes, often disadvantaging certain groups.

API (Application Programming Interface): A way for different software systems to communicate with each other. Enterprise AI tools often provide API access for secure integration.

APP (Australian Privacy Principles): Thirteen principles set out in the Privacy Act 1988 that govern how Australian organisations must handle, use and manage personal information. They cover collection, use, disclosure, data quality, security and access to personal information.

Bias mitigation: Techniques used to reduce or eliminate bias in AI systems, including diverse training data, algorithmic fairness constraints, and human oversight.

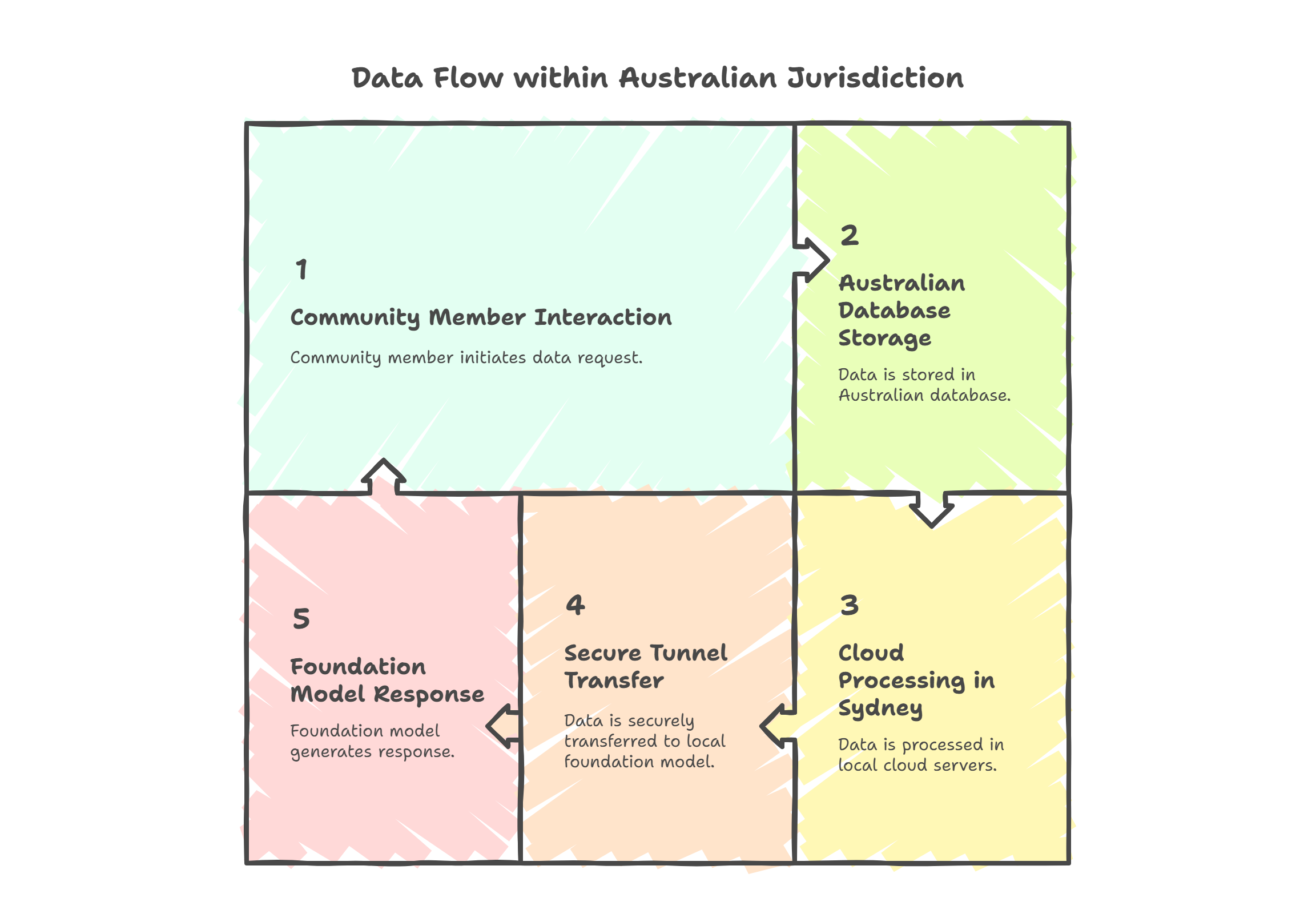

Cloud infrastructure: Remote servers and computing resources accessed over the internet, rather than local servers. Major providers like AWS and Azure operate data centres in multiple countries.

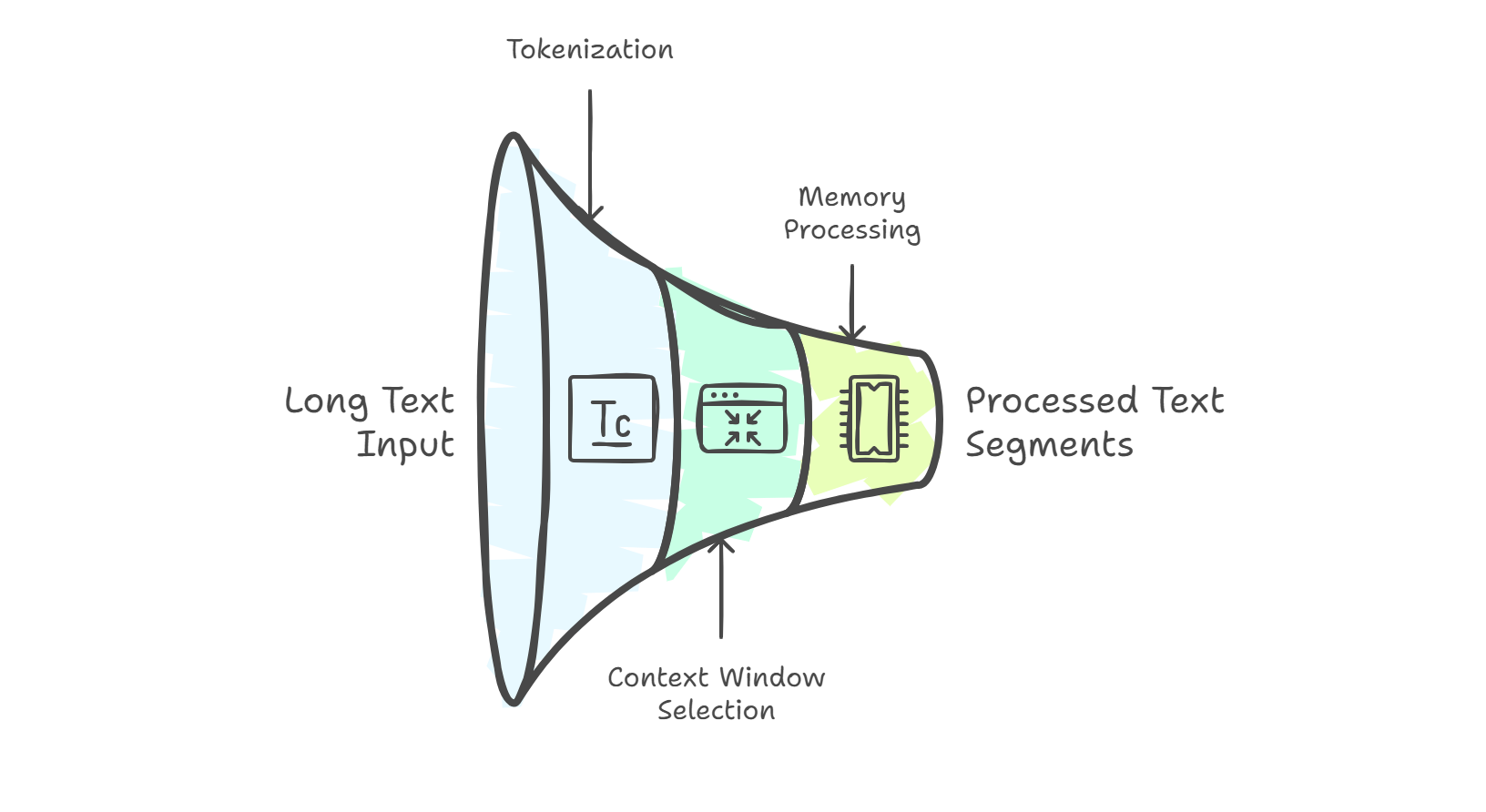

Context window: The maximum amount of text (measured in tokens) that an AI model can process at once, including your input and its response. Think of it as the AI’s “working memory.”

Data sovereignty: The principle that data is subject to the laws and governance of the country where it is physically stored. For Australian organisations, this typically means keeping data within Australian data centres.

Deepfake: Realistic but fake media (images, videos, or audio) created using AI, often used to misrepresent what someone said or did.

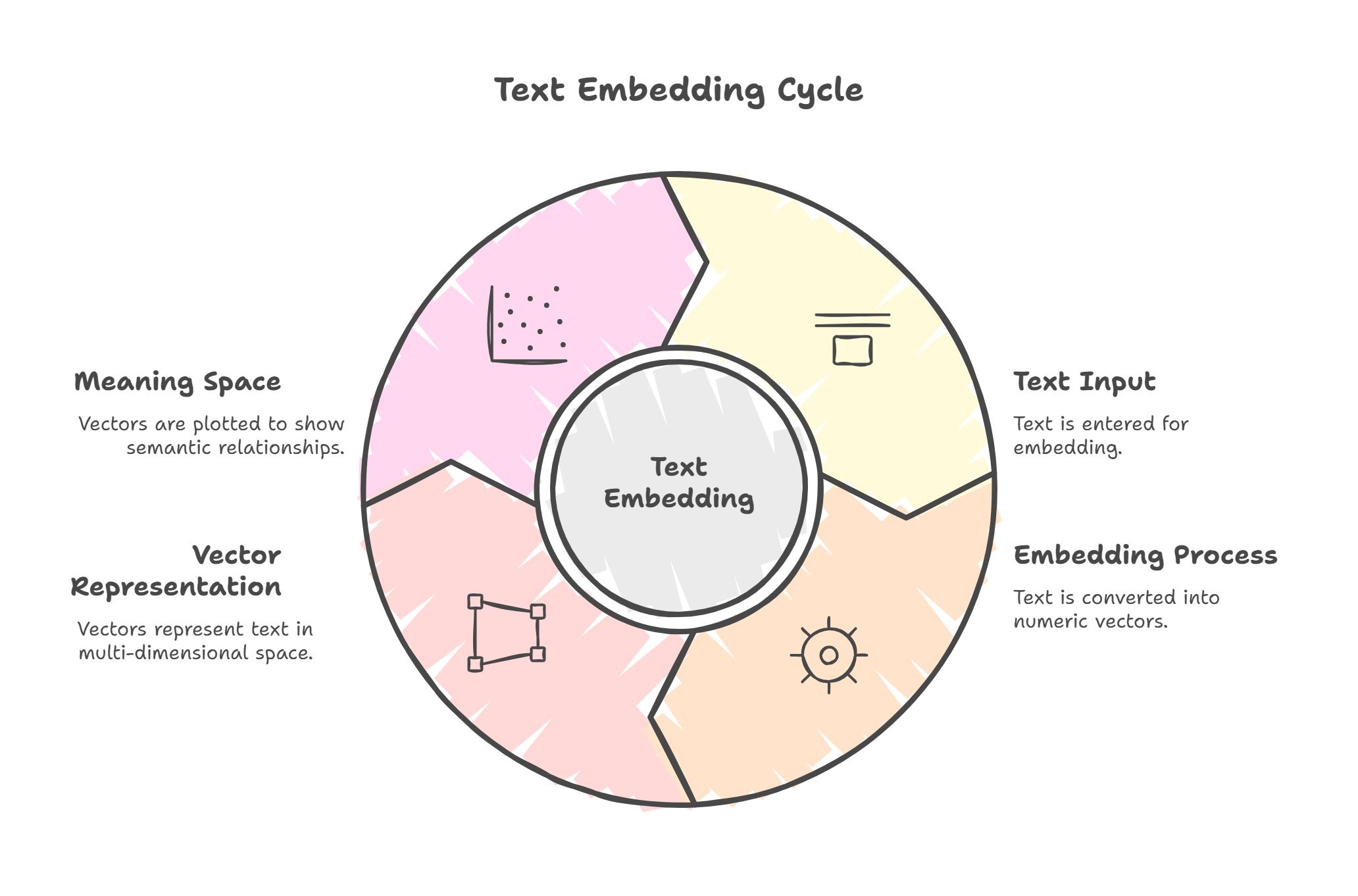

Embedding: A numerical representation (vector) of text, images, or other data that captures its meaning, allowing AI to understand similarity and relationships.

Encryption: The process of converting data into a coded format to prevent unauthorised access, ensuring information remains secure during storage and transmission.

Enterprise AI: AI tools designed for business use with strong data governance, security, and compliance features. Typically includes contractual guarantees about data usage.

Fine-tuning: The process of taking a pre-trained foundation model and further training it on specific data to specialise it for a particular task or domain.

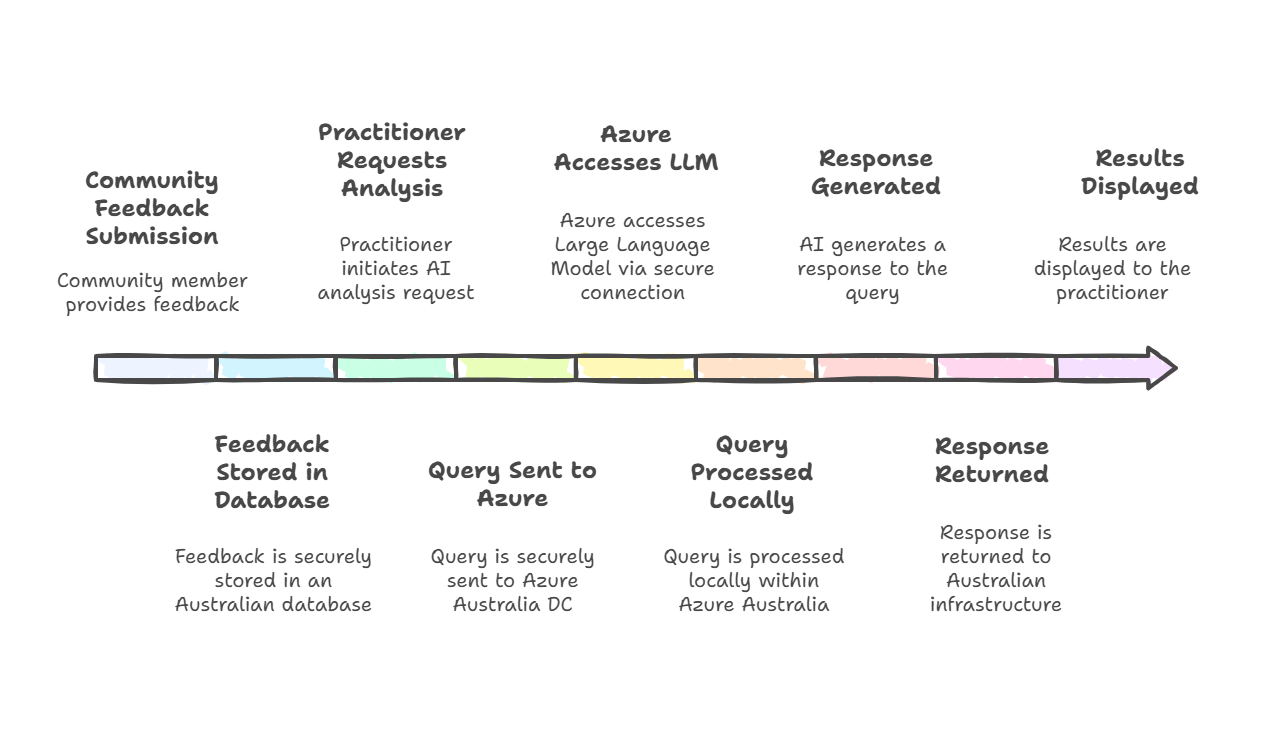

Foundation model: A large AI model trained on massive amounts of data that can be adapted for many different tasks (e.g., GPT-4, Claude, Gemini).

Generative AI: AI systems that can create new content (text, images, audio) based on patterns learned from training data.

Hallucination: When an AI confidently generates information that is false or not grounded in its training data or provided context.

Inference: The process of an AI model using what it already knows to generate an answer, prediction or summary. It is what happens when you ask an AI a question and it produces a response based on patterns it learned during training.

Jailbreak: An attempt to bypass an AI system’s safety constraints or guidelines to make it produce outputs it was designed to refuse or avoid.

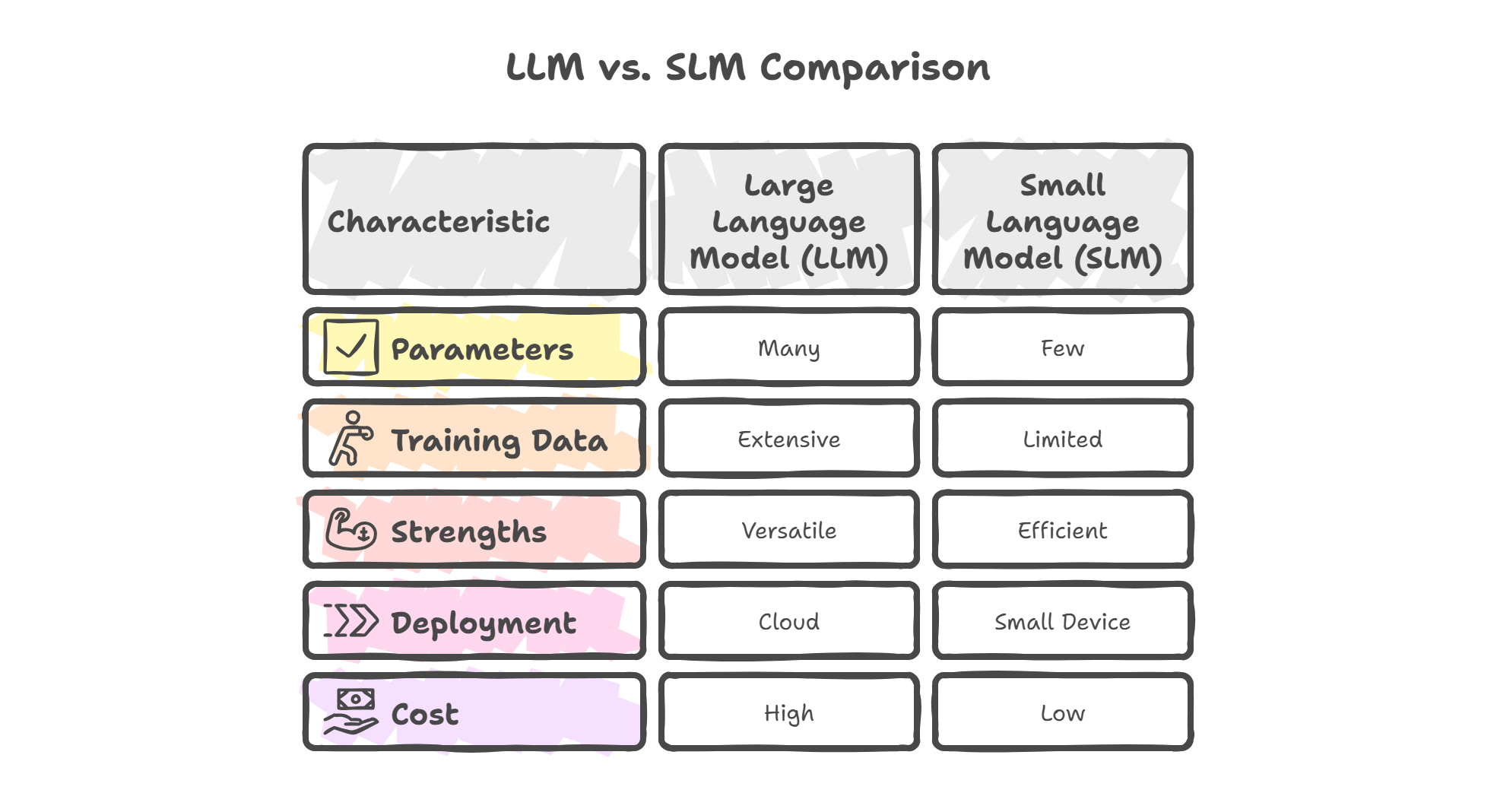

Large Language Model (LLM): A type of foundation model specifically designed to understand and generate human language, typically with billions of parameters.

Machine learning: A subset of AI where systems learn patterns from data without being explicitly programmed for every scenario.

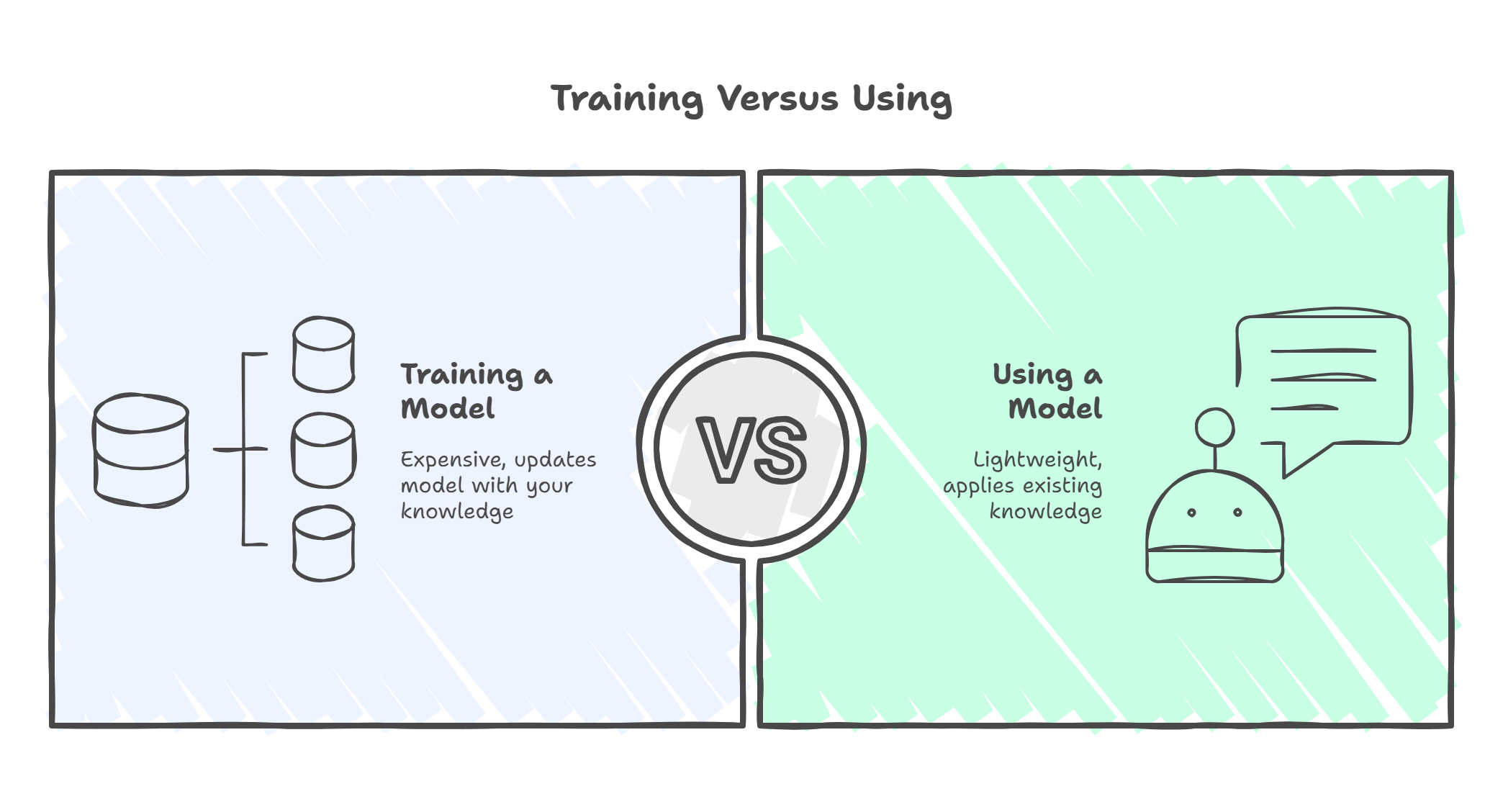

Model training: The process of teaching an AI system by exposing it to large amounts of data, allowing it to learn patterns and relationships. This is distinct from using a trained model.

Natural Language Processing (NLP): AI techniques that enable computers to understand, interpret, and generate human language.

Parameters: The internal variables in an AI model that are adjusted during training. More parameters generally mean more capacity to learn complex patterns.

PII (Personally Identifiable Information): Information that can be used to identify a specific individual, such as names, addresses, email addresses, or identification numbers.

Prompt: The input text you provide to an AI system to get a response. Effective “prompt engineering” is key to getting good results.

Prompt engineering: The practice of crafting effective prompts to get desired outputs from AI systems.

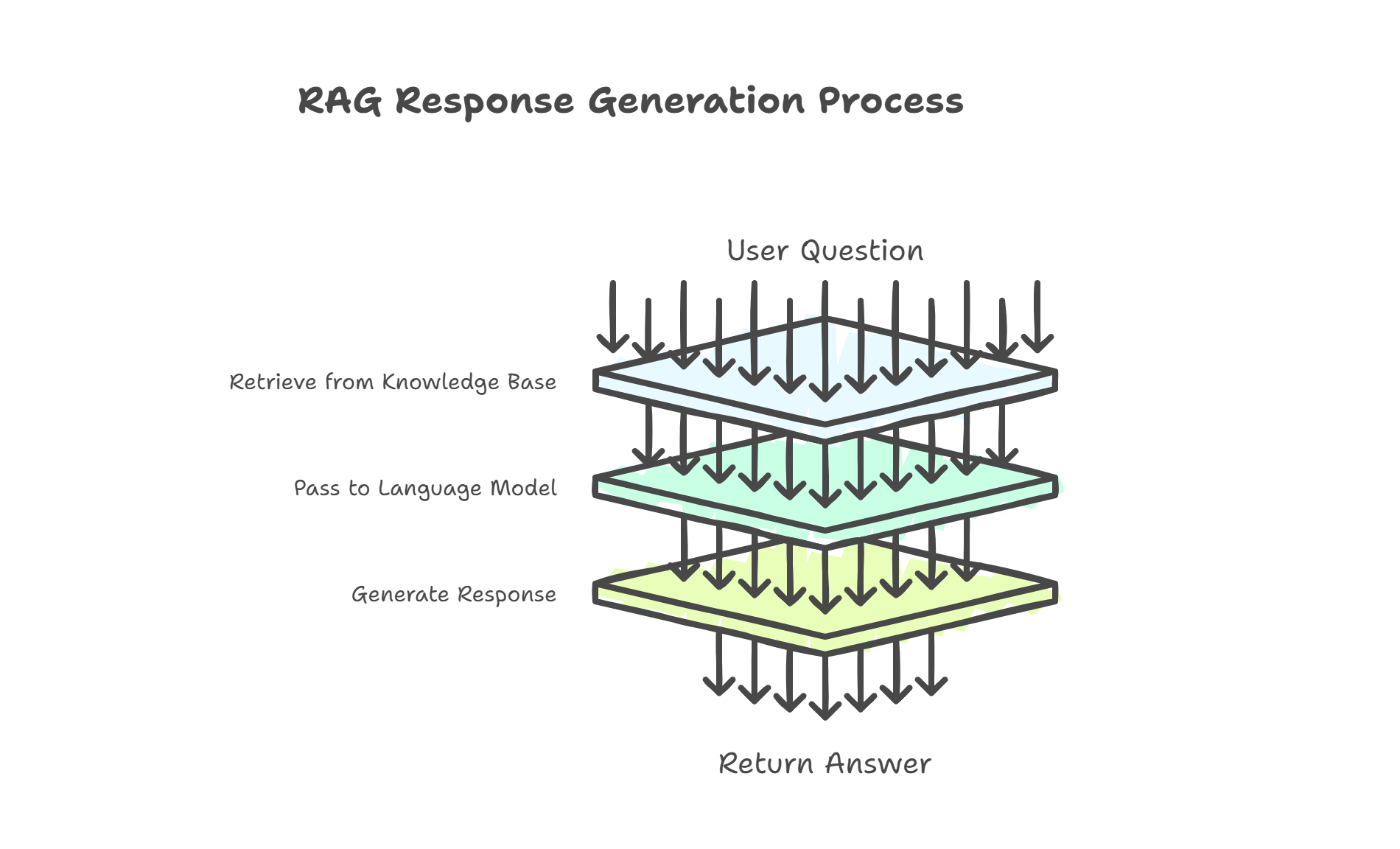

RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation): An AI architecture that combines searching a specific knowledge base (retrieval) with generating responses based on that information (generation), reducing hallucinations.

Semantic search: Search based on the meaning of words and context, not just keyword matching. Powered by embeddings.

Sentiment analysis: AI technique to identify and categorise emotions or opinions expressed in text (e.g., positive, negative, neutral).

Small Language Model (SLM): A more compact AI model with fewer parameters than LLMs, designed for specific tasks. Often faster, cheaper, and more privacy-preserving.

Synthetic data: Artificially generated data that mimics real-world data patterns without containing actual personal information, used for testing and development while protecting privacy.

Token: A unit of text that AI models process (roughly 3/4 of a word). Many AI services charge based on tokens processed.

Training data: The data used to teach an AI model. The quality, diversity, and representativeness of training data significantly impacts the model’s performance and potential biases.

Vector: A numerical representation (list of numbers) that captures the meaning or characteristics of data. Embeddings are a type of vector used to represent text.

Vector database: A specialised database that stores embeddings and enables fast semantic search.